December 2019

Globally, we regularly read news headlines reporting about occupational fraud in sport clubs. Occupational fraud is using one’s position for personal benefit by deliberately misusing an organisation’s resources or assets.

Cases of fraud in sport clubs have been reported in the media of sports clubs of netball and football (soccer) in Australia, ice hockey in Canada, tennis in Germany, and football (gridiron) in the United States. In these cases, volunteer board members (i.e., treasurer and club president) are stealing money ranging anywhere from $1,500-800,000 USD or equivalent currency.

This is not surprising given that The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (2018) reported that globally, skimming (stealing cash before being entered in an accounting system) schemes were more common in the arts, entertainment, and recreation industries than other industries (e.g., banking, manufacturing, health care or social services).

Our research team examined media stories from Australia, Canada, Germany, and the United States from 2008-2018. Occupational fraud mostly occurred through embezzlement including forged and writing blank cheques, siphoning funds, creating false accounts, and acquiring credit cards.

For example, in one case, a netball administrator from Banyule and District Netball Association (Australia) was found guilty in 2016 of siphoning $AUD209,000 over five years earmarked for junior and social players. A more recent case in the United States in 2018 showed that a treasurer admitted to embezzling over $USD150,000 from an Anchorage, Alaska youth hockey league over a span of several years.

Through these cases and many others, we see that fraud can have a negative impact on a sport club's finances, its reputation, the experiences of sport participants and volunteers, and can lead to community mistrust.

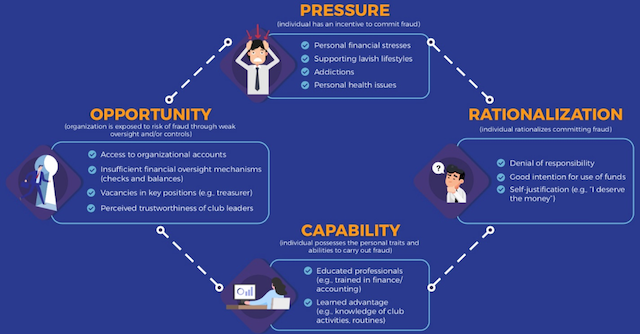

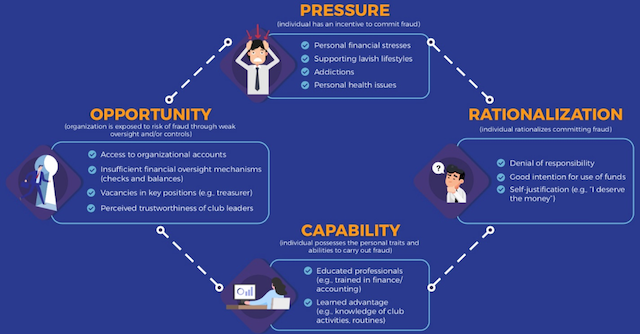

Our research has identified four main indicators of fraud that help us understand how and why fraud can happen in sport clubs: Pressure, Opportunity, Rationalisation, and Capability (see figure1).

How can a sport club prevent fraud?

Volunteer organisations place a great deal of trust in individuals who serve as board members. In sport clubs, people trust each other because volunteers in key administrative positions are usually well-respected people in the community. We do not expect that parent volunteers would steal from the club where their children play sport.

It is imperative that sport clubs develop and implement specific internal financial controls to limit opportunities for fraud and detect instances of fraud soon after they occur. Sport clubs need to adopt:

- timely and accurate financial reporting systems,

- procedures to safeguard assets,

- practices that are compliant with laws and regulations, and

- routines that efficiently utilise organisational resources.

For example, boards and other stakeholders should ensure that their sport club has:

- a separation of duties,

- requires expense and account creation authorisation by two or more individuals,

- has conflict of interest policies,

- mandatory monthly financial reporting and full disclosure to the board,

- policies for collecting cash through player registrations, concessions, and fees,

and mandatory reporting of fraud to authorities.

- regular procedures to detect any possible of fraudulent activities (e.g., external auditing, independent reconciliation of bank statements)

Increased internal controls are only effective when they are fully implemented and regularly monitored. Such controls, however, come with increased costs for the club in terms of time and energy for existing volunteers. These costs should outweigh the risks of not implementing financial controls.

It is important to note that implementing these processes will take some planning and time. Moving towards a more robust anti-fraud strategy will require education and training resources as well as system changes to both prevent and detect potentially fraudulent activities. In the end, preventing fraud in community sport will ensure the long-term sustainability of the sector and the important sport programs it delivers.

Lisa A. Kihl, University of Minnesota

Katie Misener, University of Waterloo

Graham Cuskelly, Griffith University

Pamela Wicker, Bielefeld University